How many times today have you said “I know”? Or perhaps you just thought it to yourself, alongside an inward eye roll. The moment it happens is usually the moment we stop listening, the moment we stop seeking to understand, and the moment we stop being curious.

We do it all the time. It’s a natural extension from the automatic system of our brain – designed both to protect us, but also to not have us overwhelmed by the amount of information coming in through our eyes, ears and other senses every single second. Isaac Lidsky describes it wonderfully in his TED talk – he references sight in particular, but it is equally relevant to what we hear and experience.

“To create the experience of sight, your brain references your conceptual understanding of the world, other knowledge, your memories, opinions, emotions, mental attention. All of these things and far more are linked in your brain to your sight. These linkages work both ways, and usually occur subconsciously……What you see is a complex mental construction of your own making, but you experience it passively as a direct representation of the world around you. You create your own reality, and you believe it.”

In every moment that our brain is referencing our conceptual understanding – it is referencing what we already “know”. And real killer part? We believe our reality, is everyone‘s reality. We think the world is a series of cold, hard facts, when in fact it is a huge series of interpretations. The only way to understand someone else’s interpretation of the world (an event, an experience, something that happened…) is to be curious about it, and ask.

We believe our reality, is everyone’s reality.

Beyond the obvious consequences – a whole lot of misunderstanding – the impact of “I know” goes a lot deeper.

When we know, we stop learning

We can observe a fascinating illustration of the real impact of this at Microsoft over the last six years. In this article, Simone Stolzoff looked at how Satya Nadella turned around the culture of Microsoft and its 130,000 employees after he took over from Steve Ballmer in 2014.

Ballmer’s Microsoft was renowned for internal competition, resisting partnerships, rejecting open-source software – a company where competition, internal and external, was valued much more highly than collaboration.

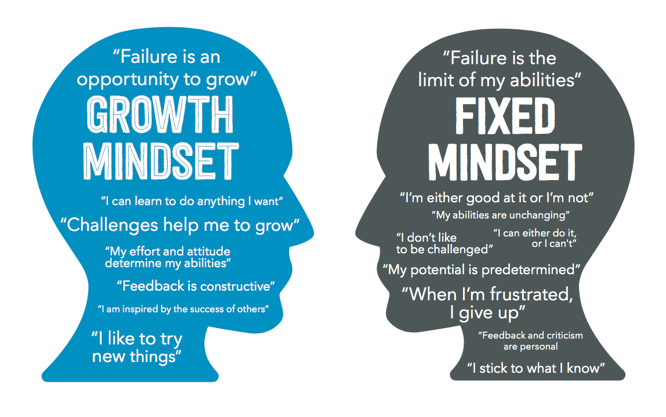

Nadella recognised a need to fundamentally shift Microsoft’s culture, and he credits Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck and her book “Mindset” as the inspiration for the change. In “Mindset” Dweck describes value of cultivating a growth mindset. Based on extensive research, she demonstrates that individuals who believe their talents can be developed through hard work and input from others (what she terms a “growth mindset”) tend to achieve more than those who believe their talents are innate gifts with finite development potential (by contrast, a “fixed mindset”).

As Nadella puts it “If you take two kids in school, let’s say one of them has a lot of innate capability but is a know-it-all. The other person has less innate capability but is a learn-it-all. You know how that story ends. Ultimately, the learn-it-all will do better than the know-it-all. And that, I think, is true for CEOs. It’s true for companies.” (quoted here)

“Ultimately, the learn-it-all will do better than the know-it-all.”

Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft

Dropping the “I know” and (re)learning to learn, constantly, is crucial to growth. And while it isn’t the only factor, since Nadella took over Microsoft in early 2014, the company’s share price has increased by more than four and a half times. Food for thought.

When we know, we don’t ask questions

Most of you will either have, or remember, or know a young child in your life. Remember how many questions they ask? I have spent hours listening to seemingly endless “why” questions from my friends’ children, often around things I not only don’t know about but it would never have occurred to me to ask!

Yet as we reach adulthood, we lose the art of questioning. In an article published in the Harvard Business Review, when the author polled their clients it was suggested that 70-80% of their kids’ dialogues with others were comprised of questions. But those same clients said that only 15-25% of their own interactions consisted of questions.

As we grow up and progress through our careers, increasingly we are rewarded for what we know, whether it is the right answer at school, or how to solve a problem at work. Questions on the other hand are typically not rewarded in the same way. For many managers and leaders, questions can become a dangerous place. Perhaps it will show them up for something they don’t know, but should? Or perhaps it will simply waste time and resources explaining things that we already “know” how to do?

Whatever the reason, when we know, we stop asking questions. That shuts down curiosity, it closes off creativity and new ideas, and limits our problem solving to familiar solutions. As leaders in a VUCA world, curiosity, creativity and problem solving are vital to flourishing teams and successful organisations.

When we know, we shut down relationships

This is another way that “I know” is damaging, and in many ways the most insidious.

Think back to the last time someone said “I know” to you. Perhaps when you were explaining something, or sharing something. Sometimes it occurs in other ways, like the leader who says “my door is always open” but never actually has time or wants to hear your ideas. That’s when “I know” becomes “I don’t want to know”.

Even if it isn’t visible, we feel the inner eye roll, the slight sigh, the sense of impatience, the feeling of being shut down. It’s like a verbal slap in the face. It causes a breakdown in relationship and communication within and between leaders and their teams.

We feel the inner eye roll, the slight sigh, the sense of impatience

I’d assert that every leader goes to great lengths to hire great people on their team, with the potential, knowledge and experience to contribute meaningfully. The hidden danger of “I know” is that it says “Don’t bring your brilliance here, it’s not wanted”. “I know” silences voices and stifles ideas. It leads to disengagement among those same team members because they learn that no one is interested in what they have to offer.

By contrast, curiosity creates a space where everyone can ask questions, encourages ideas, and increases the engagement of your team as they see the ways they can contribute in a meaningful way. It shifts a downward spiral into an upward one.

How many of us can afford to shut off our own learning, creativity, curiosity and relationships, let alone those of our team? I don’t believe any of us can, or actually want to.

So what can we do instead?

As we learn to lose the “I know”, there are a number things we can do instead. While they may be deceptively simple, they take practice, as they tend to go against our natural instincts for safety and control.

Ask more and better questions

We all know how to ask questions. Asking great questions to create the outcomes we seek can be an art form. We may ask questions to broaden out a topic, or narrow it down, we may ask to learn something entirely new or clarify something we already understand.

Above all, practice. If you’re unsure, try a question, notice the impact on you and your team. Notice also your own response – was it uncomfortable? Did it feel risky? Or maybe shameful that you didn’t know something? Try reminding yourself of that curious child, to whom asking questions is the most natural thing in the world. Like all things, it gets easier with practice.

Be curious

Curiosity is defined as “an eager wish to know or learn about something”. Rekindle your desire to learn, and stoke that fire so that it overpowers any natural instinct that you “should know”. Be curious about assumptions, about people, about ideas, about possibilities, about the world around us. I’d also add one more element to it. In my experience, curiosity also involves asking the questions we genuinely don’t know the answer to.

Be willing to not know, or to have been wrong

In my experience, this can be the toughest one to get our heads around. Our natural human instincts crave safety and control, above all we want to know. If you watched the remainder of Isaac Lidsky’s TED talk above, you’ll have heard about the concept of “awfulising”. The idea that when our brain is faced with an unknown, it tends to fill it with the worst possible option.

Being willing to not know takes courage and vulnerability

Being willing to not know takes courage and vulnerability. It might trigger feelings of shame, discomfort and fear. However, one of the most powerful things we can do as a leader is show our own humanity, our own vulnerability, as it creates a space for others around us to do the same. Being willing to not know is a key behaviour to create a learning environment, a psychologically safe environment, and a place where new ideas are truly welcomed.

The place to start is awareness. Notice your own places where you just “know”, and get curious. You might just uncover something amazing.